The following extract is taken from the informative yet perplexing book entitled “The Story of Silbury Hill” (Jim Leary and David Field, 2010, English Heritage). We start on page 39 for this, the first and most important instalment of this posting.

The authors are relating the later stages of the 1849 probe, then under the direction of John Merewether, Dean of Hereford Cathedral, involving lateral tunnels that began in the side of the mound, approximately at ground level.

“Merewether, who had visited the excavations en route to the meeting and taken a room at the Waggon and Horses at Beckhampton, remained to observe progress and instructed that lateral excavations should be made to both east and west. A number of silicified sandstone boulders known as sarsen stones were encountered in one of the lateral excavations on the east side, and ‘they were much worn and similar to those found in the surrounding fields’ (ref 35), Merewether reported that they were:

“placed with their concave surfaces downwards, favouring the line of the heap … as is frequently seen in small barrows and casing as it were the mound. On top of some of these were observed fragments of bone, and small sticks, as of bushes … and two or three pieces of the ribs of either the ox or red deer … and also the tine of a stags antler.”

Can these highly specific details, ones that at first sight would seem to have no rhyme or reason, be accommodated into the latest update of this blogger’s thinking re Silbury, namely that it served for composting of human (probably) soft tissue remains, possibly the heart only.

Link to this blogger’s recent article on the ancient-origins site.

See also the follow-up posting, posted just yesterday (April 11) that immediately precedes this one.

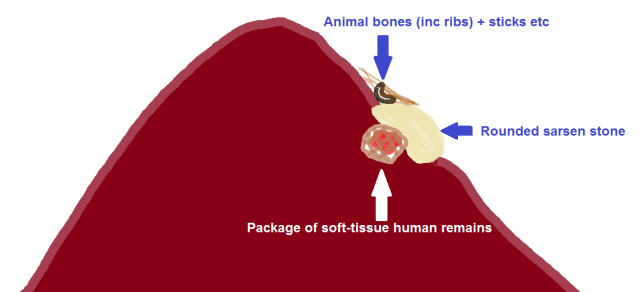

Yes, I do believe they can, and this highly schematic diagram, cobbled together with MS Paint, shows how:

Captive earthworms (see author’s previous postings) have been omitted, not being central to the sarsen narrative!

The sarsen was needed to protect the interred soft tissue remains from animal scavengers. The sarsen was implanted concave-side down so as to provide a cavity that would encapsulate most or all of the interred package. Why the animal bone, sticks, ribs etc? Inevitably there would be an occasional animal intruder to the site – a dog, fox, rodent etc – one with a keen sense of smell, picking up the presence of flesh. It would sniff around the sarsen initially, and maybe attempt to lift or paw away under the stone, but its weight and rounded shape (yes, we’re told elsewhere the sarsens used tended to be rounded) would defeat it. That would leave it with little option other than to be content with a ‘consolation prize’ in the form of a few animals ribs etc. Even then, the ‘free gift’ would have to be extricated from a thicket of sticks, and being something that required patient chewing would probably mean the animal needing to vacate the mound to work on it laboriously but safely elsewhere. End-result: the interred package stays intact until Mother Nature, assisted by those captive earthworms, has done the necessary, and the Neolithic bereaved can be content with the thought that the soul of the deceased has been released from the mortal remains. The latter needless to say finally becomes integrated back into something that is indistinguishable from rich, wholesome-smelling soil.

Further additions to follow in a day or two, chiefly to ‘tie up some loose ends’ re the likely mode of packaging of the mortal remains, the use of rough-hewn rather than rounded sarsens in the outermost chalk revetment of late-stage Silbury etc.

Postscript: Wow, I’ve just chanced upon this article from the Independent published 9 years ago, in which it’s proposed by Jim Leary and others that Silbury is a monument to the souls of the departed, and that each soul is represented by – guess what?- yes a sarsen stone!

Now if I could just persuade JimL to go back inside and take a closer look at some of the “organic” material that he reported seeing inside the mound, like layers of “black soil”, “mud” etc. They might not be be recognizable as 4,500 year old human remains, but there might be ways of demonstrating that they represent accumulations of worm casts derived therefrom. There’s a Silbury literature on the calcite granules of worm casts that were used for radiocarbon dating that I’ve so far not discussed. Perhaps I should, especially as I appear to be the only one thus far to have proposed a direct cause-and-effect relationship between (on the one hand) those mortal remains, long since “disappeared” – if as I believe it was soft tissue only that was interred, not bones – and those humble worm casts on the other, constituting a greater proportion of the internal dark layers of Silbury Hill than realized thus far.

Second instalment: Wed April 13

My quoting for the L&F book continues on the same Page 39, with reference it seems to the 19th century Merewether’s observations at the very heart of Silbury, i.e. the end of the lateral excavation tunnel. Yes, it seems that what follows relates to the central mound, the first-formed one with its abundant turves, snail shells etc, presumably what L&F describe as the ‘organic mound’

My bolding:

“Merewether also noted that there were ‘great quantities of moss still in a state of comparative freshness’ (Ref 37) and that it still retained its colour.He believed that this material, together with the freshwater shells, had come from a moist location and thought that it must have been derived from the west, north or east sides of the Hill where the Beckhampton Brook flowed past the foot of the mound. Sealing the turf stack was a dense black layer of organic material containing fragments of small branches and emitting a peculiar smell. In addition, fragments of what he thought were plaited grass or string were discovered in this organic deposit. This was not recorded in any of the later excavations and is likely to have been fungal mycelium, probably introduced in (the) 1776 (excavation, vertical shaft).”

Passing lightly over the “peculiar smell”, which would certainly betray the presence of something organic, something had maybe composted under less than ideal conditions perhaps (anaerobic?) and not necessarily of plant origin (need I say more?) we find that fascinating but infuriatingly brief reference to “plaited grass or string” which is immediately explained away as “fungal mycelium”.

I guess we’ll never know whether it was plaited grass/string or fungal mycelium, given the description applies to the 1849 investigation which was unlikely to have preserved material for future generations to re-examine (or am I being overly pessimistic?).

However, I am not prepared to be summarily put off the scent (no pun intended) regarding what I consider an important possible clue as to the real purpose of Silbury Hill. Given there are said to be scores, probably hundreds of sarsen stones in the interior of the Hill, and given I consider each to be the marker for an interment, as per diagram above, then here’s a prediction. (We science bods are given to making predictions, considering them to be the sine qua non of the scientific method):

Behind each sarsen stone there will be found at the very minimum either (a) a cavity or (b) a sizeable amount of darkish soil which under the microscope will be found to have the signature of a worm cast – namely calcite granules or (c) more remnants of what appears to be plaited grass or string, and which indeed will be found to be plaited grass or string or (d) combinations of two or more from (a) to (c).

Why? Because a package had been interred behind each sarsen some 4,500 years ago, which contained human mortal remains, maybe as little as the heart of the deceased, maybe more. That ritualistic consignment had been brought to the Silbury composting site by the relatives, probably in a simple receptacle like a basket or string bag, enveloped in turves from the deceased’s home, and probably accompanied, intentionally, by a number of earthworms, because that I propose is how things were done in Neolithic Britain in that era, and for very sound practical reasons (which will be reiterated later).

Final instalment to this posting- started 11:00, Wed 13 April

I have been keeping this one till last, since it’s arguably the most tendentious, yet at the same time focuses on an aspect of those hugely significant sarsen stones that cannot be ignored. Indeed, it’s so tricky, so tentatative, or as some might later say, tendentious, that it will be written in sub-instalments.

The starting point of this section is in fact the end-phase of Silbury construction, the capping off with chalk, once the decision had been made that the mound had reached its maximum capacity as regards interment sites. That was an inevitability of course, given that the mound is conical, not cylindrical, with progressively less ‘floor area’ as it ascends, to say nothing of increasing physical effort needed by the bereaved to ascend to the later working levels. What happens then? Well, it’s my guess that the last generation of Silbury builders looked at what had evolved from small beginnings, with no preconceived plan to build a dramatic landscape feature, and thought: “We can’t leave it as an incomplete, untopped-out eyesore. It’s in fact well on its way to becoming the 8th Wonder of the World, correction, the less-anachronistic equivalent. So let’s do the decent thing and finish it off artistically. How shall we do that?”

Well, the rest as they say is history, and that involved cutting still more chalk from around the base and moving it to the top, but that was and could not have been a mere dumping operation. It involved the construction of the so-called chalk revetment walls, aka chalk rubble walls. These encircled the mound, leaning inwards for strength and support, and allowed for free drainage of rain water, said to be a major reason for why the Hill exists to this day. Having thus briefly introduced the “chalk revetment wall” one is now in a position to introduce an element of the unexpected, namely a conjunction of chalk AND sarsen stones and/or boulders into that wall. That involves going to Pages 110/111 of L&F to read Richard Atkinson’s description of the chalk revetment at the uppermost levels of Silbury Hill. Stand by then folks for some more cut-and-paste, correction, laborious manual copying from the book into my word-processor, then pasting.

Quote (lightly edited): my bolding

“As the final remnants of the topsoil and subsoil were … shovelled and scraped away from the main … excavation trench on the summit, the tops of these chalk revetment walls became visible.

A small patch within one of the walls, however, looked distinctly different, and as excavation proceeded … the reason became obvious. Rather than using chalk rubble to build the wall, this small area (3m x 5m) was made from broken pieces of sarsen rubble.

Lying alongside them were pieces of picks made from red deer antler. These sarsen stones are extraordinarily heavy, certainly when compared to similar size chalk blocks… Further these sarsen fragments seem to have been deliberately placed next to the antler. A closer examination of Atkinson’s archive slides from his 1970 excavation, revealed similar clusters of sarsen stones within the walls dotted throughout his much larger trench … this strange phenomenon seems widespread throughout the later construction phases of the mound. Indeed, one is visible eroding out of the present pathway close to the summit…

The sarsen fragments on the summit were different to those seen within the tunnel. The fragments from the summit were formed largely of broken pieces … contrasting with the whole rounded boulders recovered from inside the mound…

So why the sarsen stones in a smallish part of the revetment, and ‘out-of-character’ broken rather rounded ones?

First, what would be surprising would Silbury having been finished off entirely with chalk, leaving no external and visible sign of its role in some 100 years or so of late Neolithic development. It was after all a sacred site within a pagan but probably spiritual society, one that revered the dead and went to some trouble to give them – or a symbolic part thereof – a proper send-off.

Given the special significance attached to sarsen stones as putative markers for each interment, what better way to discreetly flag up the mound’s raison d’etre than to incorporate some sarsens into the external revetment.

It’s admittedly a token gesture at first sight, and more so given the sarsens would only have been clearly visible at the top. Wouldn’t ground level have been a more logical place?

Yes, probably, so might there have been a different rationale? Maybe. The capping off would have been done when there was still space for a small number of final interments, maybe as few as one or two. Might the sarsens have been intended as a portal through which the final installation would or could be made? Maybe a ‘future insertion for someone very important was envisaged, given the dominant and commanding position at the top of Silbury.

Why use sarsens with irregular rather than rounded shape? Let’s dispose straightaway of the idea that all the rounded sarsens had been used up. If that were the problem, the rounded variety would simply have been brought in from out of area. It hardly needs saying that Neolithic folk thought nothing of lugging megaliths over vast distances. Even if one’s sceptical at the idea that Stonehenge’s bluestones were translocated from the Preseli mountains of Wales to Salisbury Plain, the even larger sarsens in the outer circle of standing stones allegedly were transported from the Marlborough Downs, on Silbury’s doorstep but some 25 miles from Stonehenge.

There’s an alternative explanation. Had rounded sarsens been used then that portion of revetments could have been mistaken for the site of an occupied interment. Choosing broken irregular sarsens would have signalled the presence of an access point for a then as yet unutilized location within the mound.

Almost there : just a little more needed – expect it to arrive in the next day or two.

In the next post I shall be addressing the 64000 question: why the theory presented here continues to be ignored and indeed shunned? I shall be commenting on the inappropriateness of judging Neolithic societies by modern day standards. I shall be defending the manner of disposing of the dead proposed here as one that was rooted firmly in the realities of living on the chalk uplands of Wiltshire where there were no easy options. We are discussing an era of human history that preceded the Bronze and Iron ages – thus no metal tools to dig graves in bedrock chalk, and an increasingly deforested habitat, which while attractive for early pastoralists, was one in which timber was too valuable to be waste on cremation via funeral pyres, being needed to stay warm and alive, especially in the winter months.

……………………………………

Addendum: March 16, 2018

Have decided to add the following image as an addendum to ALL my Stonehenge postings (some 24 in all, here and on my sciencebuzz site). Why not – since it’s my considered answer to the ‘mystery’ of the monument’s peculiar architecture, the conclusion to some 6 years of deliberation?

Reminder*

I say Stonehenge was designed as a giant bird perch, a ceremonial monument dedicated to ‘sky burial’, i.e. soul release from mortal remains to the heavens via AFS (avian-facilitated skeletonization, considered the height of fashion (and practicality) in Neolithic-era 2500BC! The stripped remains were then cremated, so an apt description of Stonehenge might, as previously suggested, be PRE-CREMATORIUM.